JP Morgan CEO Jamie Dimon’s letter to shareholders.

Change Healthcare IPO filing

Essential thoughts on US stocks, financial markets, M&A and IPOs…and some other random topics

JP Morgan CEO Jamie Dimon’s letter to shareholders.

Change Healthcare IPO filing

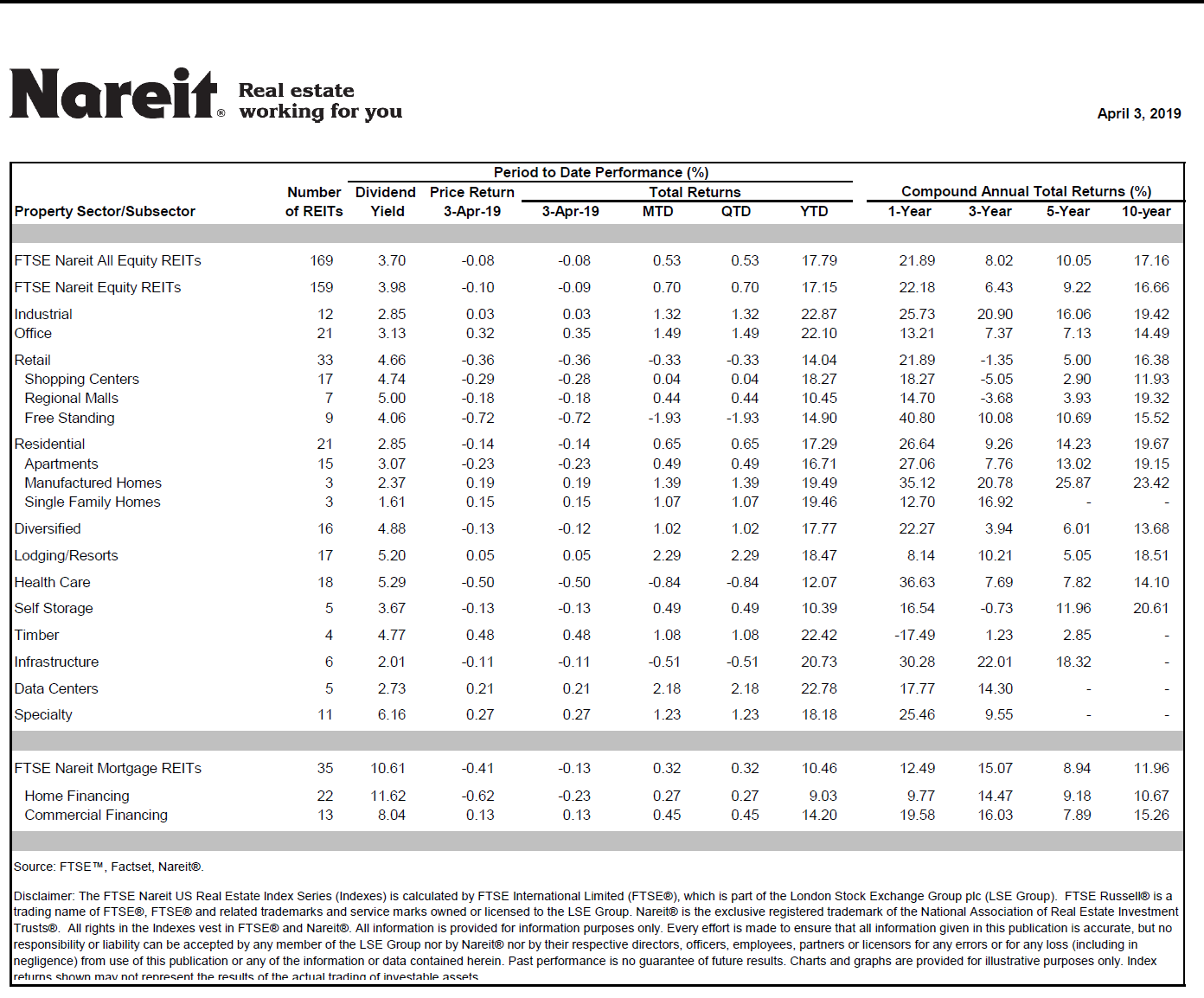

REITs are showing a 17.8% year-to-date return led, by industrial REITs and data centers tied to e-commerce and cloud computing trends. Source: NAREIT.

UPDATE: LYFT PRICED AT $72.

The IPO of ride-sharing unicorn Lyft is likely (this afternoon) to price at the top end of the upwardly revised US$70-$72 range or better after drawing huge demand from investors during the two-week roadshow.

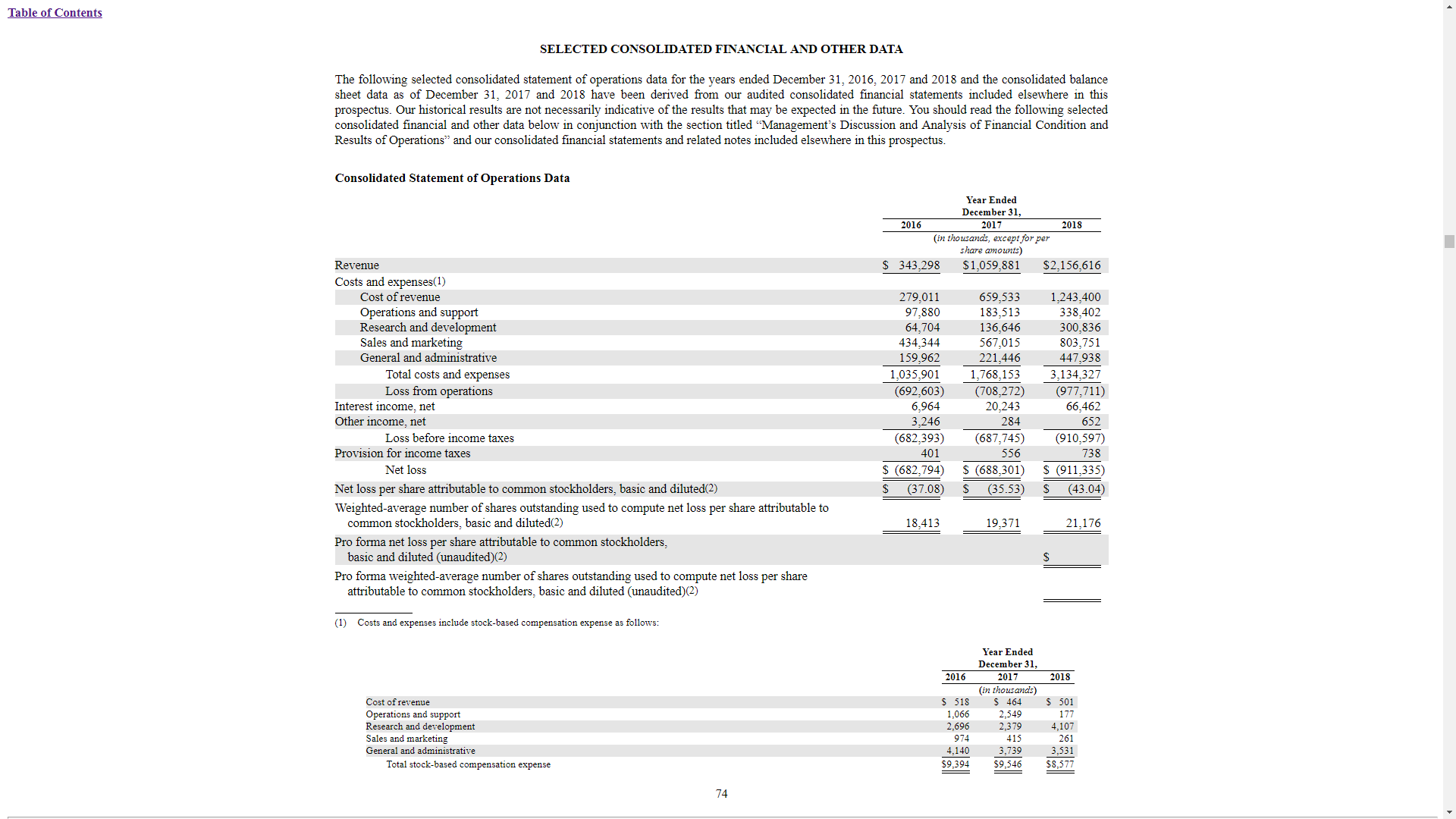

Though there’s plenty of angst about Lyft’s cash burn and the fact it lost US$911.3m last year, at this point it simply doesn’t matter.

Reservations about the ride-sharing business model – in short, give it away if you have to, but get to scale as quickly as possible – and various regulatory issues are well-founded. But in Lyft’s case, these are questions for another day.

IPO investors want to invest in growth and companies that are doubling their top-line at scale don’t come along often.

Even if the overall market takes a breather here, companies that are growing at rates well in excess of the broader market and carving out new industries should fare relatively well.

This is probably why – somewhat counterintuitively – high-growth (tech) and defensive stocks outperformed in Q1, a quarter that saw the Federal Reserve become much more dovish and recession fears ease even with trade concerns top of mind.

Though Lyft’s financials are splotched with red ink, the growth is undeniable as is the potential size of the ride-sharing market if Lyft and Uber and others succeed in killing off household ownership of the automobile.

Anyway, that’s the potential. At this stage it is almost pointless to predict whether this happens and whether some other unicorn emerges with a even better model to deliver what Lyft calls “transportation-as-a-service”.

The IPO roadshow was standing room only and virtually everyone who got a chance put in an order.

Lyft made it clear in its filing it was not focused on short-term profits, or profitability at all, but investors won’t be too worried as long as the company is growing.

The lingering question is whether Lyft or arch-rival Uber, soon to follow with its own IPO, is the better bet.

I heard someone say yesterday that Lyft is just a smaller Uber with better PR. Of course, there are some differences between these companies in their geographical reach and the extent of their focus on other businesses, but it is true the ride-sharing experience is close to identical for customers.

Given the financial profile of the industry, that means the company with the deepest pockets is likely to have the most success.

Because of its larger size, Uber should be better placed to raise additional capital (equity, debt, convertible debt etcetera) and outlast Lyft in any extended price-based market share war in key cities.

That said, there may be room for both and investors at the moment clearly figure that Lyft is a great bet on the ride-sharing phenomenon.

Jeans maker Levi Strauss & Co surged 31.8% on debut today after pricing its IPO above range for base proceeds of $623.33m, the most confident sign yet a new-issue revival is under way after a disastrous start to the year.

Levi Strauss is the biggest IPO of the year so far and comes ahead of chunky near-term offerings such as Lyft, Tradeweb Markets and Change Healthcare, and maybe Uber (looking like April timeframe) as the biggest of them all.

The demand for Levi Strauss was clearly very strong, even stronger than you might expect for a company up against the vagaries of the fashion retail business.

This is a brand that has stood the test of time, the company has some growth (14% at the top line last year) and has been able to expand its margins by selling direct to the consumer, the trend that is likely killing off large parts of the traditional retail sector.

One reservation – apart from whether the company’s current growth is really sustainable – is that the controlling Haas family sold some of its stake at the IPO and may not be done. The prospectus is not explicit about their plans, which is probably intentional, but it means that a secondary sale is not out of the question later this year.

As investors counted their winnings, it was easy to miss that another IPO scheduled for this week, human resources software company Alight, opted to defer its IPO ahead of pricing tomorrow night.

Alight is backed by private equity firm Blackstone, which pulled the plug as investors showed reluctance to pay up inside the $22-$25 range for a company that is not growing as fast as the usual software IPO.

In fact, the way the financials are laid out in the prospectus, it is difficult to make prior-year comparisons.

The outcome shows that investors are not in a mood to buy anything, despite the dearth of IPOs so far this year. This could also be read as investors being extra cautious about current valuations, including those of the peers against which Alight was valued.

The other mark against Alight is its private equity backing, and it is a legitimate question whether the sponsor-backed IPO market, a major avenue for the monetization of sponsor investments, is broken.

Though Blackstone was able to bring a large number of its US portfolio companies public in the past five years, it hasn’t done so many in the past year or so.

The same goes for the other big private equity firms, now the center of much power on the Street (in part because they pay the biggest fees to investment banks).

The big miss last year was Apollo Global Management’s IPO of home security firm ADT. The deal priced well below range but ADT stock still trades at price less than half ($6.57 today) the level at which it went public at ($14) in January last year.

In fact, the private equity firms have produced some great public companies over a longer timeframe, but it is often the case that they perform poorly early on (2015’s First Data IPO is another classic example) because private equity firms on principle do not sell assets cheap.

Private equity firms have also gravitated to traditional industrial companies that can be bought cheap for their lack of growth but still generate consistent enough cashflow to support their financial engineering – that is, the pay down of hefty debt loads.

These companies typically come to market with high debt levels as a legacy of their leveraged history, though usually IPO proceeds are applied to bringing down debt to more manageable levels.

Change, a health IT company formed from a deal with drug distributor McKesson, is the next Blackstone portfolio company looking to get public. It is said to be looking to raise $1.5bn-plus but the Alight outcome suggests it is no fait accompli.

Uber or Lyft? Which to use is a question that has dogged New York’s ride-sharers for years.

With both poised to go public in the next month or two, the battle between these two bitter arch-rivals is about to extend to winning over the hearts and minds of the investment community. Things could get really interesting.

On Friday (March 1), Lyft started the clock for its IPO by filing publicly. It registered confidentially with the SEC on December 6, so it is already well advanced through the SEC review process. From all reports, the IPO roadshow will begin March 18 (it has to be at least 15 days after the public filing). With a standard roadshow, the deal should price on either March 27 or 28 before the stock debuts on Nasdaq the following day.

Cue plenty of (valid) commentary about the company’s cash burn and lack of profitability.

Multiply the media frenzy by four (?) once Uber files, which could well be in the next few weeks because (probably not coincidentally) it filed confidentially on the same day as Lyft.

Since it is more complex, larger and a more global beast, and the SEC is going to look really bad if it doesn’t work, Uber’s filing is said to be getting more scrutiny from the securities watchdog.

There is no doubt that ride-sharing is a social phenomenon that promises to revolutionalize and is disrupting transportation, and, depending on your perspective, for better or worse. Less clear is whether the numbers stack up.

Lyft lost $911m last year (net loss but adjusted Ebitda is a similar amount) and burned through $281m of cash (based on its negative operating cashflows).

This is bracing stuff compared with the average IPO, but Lyft also doubled sales last year. Getting to even greater scale as quickly as possible, and outlasting other upstart competitors, is the priority.

I’ve seen IPOs that were growing that fast AND were very profitable at the time of IPO, but, counterintuitively, this can be a sign a company’s best days are behind it. The 2015 IPO of fitness band maker Fitbit is a good example. It presented some of the best financials ever seen for an IPO, but the deal came at or near the peak of its growth just as a host of competitors were able to come into the market with significantly cheaper products.

Though the IPO went well and the stock traded up initially, the deal didn’t stand the test of time. Fitbit stock now changes hands at just 30% of its IPO price.

More important for new investors is what Lyft’s financials will look like after this year and the coming years.

I thought the most interesting part about the filing (apart from the actual finances and the litany of legal actions the company faces) was the final part of the letter to investors from the co-founders Logan Green and John Zimmer.

“If we told you we were building the world’s best canal, railroad or highway infrastructure, you’d understand that this would take time. In that same light, the opportunity ahead requires continued long-term thinking, focus and execution. In order to best deliver long-term value, we will drive the business forward with three key principles:

| “1. | We first serve drivers and riders. |

| “2. | We prioritize the long-term health of the business, over day-to-day reactions of the markets. |

| “3. | We thoughtfully balance investments in growth and profitability considerations, while deliberately leaning more towards growth (especially in these early days).” |

Maybe it is just me but that doesn’t read like a company that is going to swing into profits anytime soon.

The question is: Does it matter? Much like Amazon, as long as the company continues to grow at above-market rates, it will be able to access capital and fund its growth without generating positive cashflow/Ebitda/profits etc.

That growth is the same reason why investors will swarm this IPO, the caveat being we don’t know the valuation.

At the mooted valuation of up to $25bn, Lyft would be coming at 12x 2018 sales or thereabouts (actually less using an EV/sales multiple that subtracts cash and equivalents from market cap used in the numerator)

The multiple comes down quickly if the company can continue something close to the current rate of growth, a doubling of its net revenues last year to $2.16bn.

It is a sure bet that market models will factor in high-growth for the next few years (50%-plus) at least.

Given there are not many growth stories like this around, this alone should ensure the IPO is heavily oversubscribed and (maybe) opens strong.

But whether these forecasts are right are a completely different thing.

Further out, things could be challenging, the fear being this could be more of a Blue Apron than Amazon-type situation. Blue Apron also had growth but huge cash burn in a new market (meal-kits) where the number of competitors offering introductory discounts multiplied quickly.

Lyft is actually the first-mover in ride-sharing but is dwarfed by Uber and there are quite a few other competitors too (Juno and Via in the US for starters).

So far ride-sharing is not like search (Alphabet/Google) and social media (Facebook) that have pretty much been winner-take-all markets, and not necessarily for the first-mover (Yahoo, MySpace).

But it could be, which is why Uber and Lyft are going public at the same time in a race to tap out equity capital providers first.

Talking to a number of NYC drivers in the past few days, it seemed they were all either using Uber exclusively or using both, but not Lyft exclusively.

According to one, using Lyft alone was not enough to make a living, which just highlights how Uber has the upper hand in markets like NYC and probably elsewhere too.

So even though Lyft has more room to grow by virtue of its smaller size, those that doubt the industry’s economics will sustain multiple players are going to back Uber instead.

As long as it keeps growing, does it really matter?

Shares of e-commerce giant Amazon fell 5.4% to $1,626.23 today in the aftermath of Thursday’s Q4 earnings release.

The release showed Amazon’s net sales rose 20% to $72.4bn, while net income was $3bn or $6.04 a share. These numbers beat Street estimates (slightly) but Amazon’s Q1 estimate was a little light.

Amazon told investors it expects Q1 2019 sales of $56bn-$60bn, 10%-18% above the $51bn number it reported in Q1 2018.

The stock reaction proved an open invitation for critics to recycle their usual complaint about this stock – its sky-high price/earnings ratio (80 on a trailing 12-month basis) and its lack of earnings versus relatively low PE companies like Apple.

As someone who naturally sympathizes with value investors, I am not here to argue that Amazon is a cheap stock.

And it shouldn’t really surprise anyone that the stock eased a bit after breaking through $2,000 a share in early September. The stock crossed the $1,000 mark less a year earlier. You can’t underestimate gravity.

Even with its recent decline, the stock is still showing a gain of 427% since the start of 2015. Anyone who is a long term holder of this stock is not complaining. I am pretty sure about that.

And I hate to break it to those who focus on Amazon’s lack of earnings and enormous PE. To state the obvious, this is not the basis upon which investors are valuing Amazon stock. If it was, then it would never trade this high in the first place.

What Amazon does have in spades is growth – consistent growth and growth from a large base – and a large addressable market. And whether you want to express that in a explicit valuation metric or not, this is the basis upon which people are long the stock.

First, let’s look at Amazon’s growth record. I was wondering today just how consistently Amazon grows its sales so I took a look at the company’s investor relations page. The page has four years of quarterly earnings conveniently displayed.

You may or may not be surprised to learn that Amazon has grown its revenues in every single one of those 16 quarters and the year-on-year growth rates ranged from 15% to 43% in those quarters and averaged nearly 28% over that period.

Note that at times when it seemed Amazon’s growth rate was slowing in percentage terms, it was able to come back and report faster growth in later quarters.

Obviously, this unbroken run of growth means that Amazon has only got bigger and bigger. The law of large numbers alone should be making it harder and harder to keep up these 20% growth rates.

I would hazard to guess there are not many companies in corporate history that have grown that fast at that size with such consistency, though of course Google (I haven’t done the numbers) probably doesn’t look too bad either given the gold mine that is search and Microsoft seems to have turned over a new leaf in recent years.

The difference between Amazon and Google/Alphabet, however, is the size of their addressable markets. Google is mainly attacking the advertising market. According to one report I found on the internet, annual advertising spending globally is $500bn-plus.

Amazon is disrupting retail (and web services and a few other things – including advertising too – but let’s not overcomplicate it).

Now there is a lot more to retail than the goods that Amazon sells and there will be corners of retail not even it will ever reach, but this is a $20trn-plus market, that is, many times bigger than the advertising pie. Within that, retail e-commerce is a $5trn market but one that is obviously going to grow faster than retail overall.

The sheer size of that opportunity, still, is another reason why Amazon trades where it does and Google trades at 27 times.

I am not saying Amazon won’t stumble or can’t go lower here. Like all large companies, it’s inevitable that it will have some troubles at some point.

But not all of its growth is organic and it is able to acquire selectively from a position of strength. The purchase of Whole Foods Market last year has clearly bolstered the top-line.

The price action in recent months show it won’t take much bad news to put a dent in the stock, but neither should it when the stock has risen so fast so quickly. And if Jeff Bezos was ever to get run over by a bus, it would obviously not be pretty.

But Amazon’s demise has been predicted many times before and there are good reasons why those predictions have been wrong. One is that customers love the business because it has customer-centric approach that puts so many incumbent companies to shame.

My point is it is getting old to go on and on about Amazon’s PE. Get back to us when this company stops innovating and stops growing its top line but I suspect that won’t be for a while yet, and if it looks like happening this company can buy some growth too.

I don’t own the stock but did at $180.00 (when was that?) and sold at $200.00 after reading one too many articles on Seeking Alpha about how overvalued it was. And I regret it to this day.

Can’t speak for this one but his last book was great!

Try the link here.

One trader I talked to this week said no one believes it, but it is rare for the stocks to bounce back as rapidly as they have since Christmas Eve (S&P 500 up 10%). The above post puts some data around that.

Source: Refinitiv

The above is an excerpt from Refinitiv’s weekly earnings report.

The bit that investors need to keep an eye on is the earnings growth rate for the next four quarters.

The next set of earnings reports should show S&P 500 companies grew earnings per share 15.1% in Q4 2018 (look for the number to end up higher as the real numbers come through).

But you can see the Q1, Q2 and Q3 numbers for 2019 are expected to fall back into the single digits, partly a function of earnings cycling the corporate tax cuts last year, as mentioned here previously.

Some strategists estimated the tax cuts added around eight percentage points to 2018 earnings growth so it shouldn’t be a surprise that growth is harder to come by this year. But that has nothing to do with the companies doing it tougher or the economy going into recession. That, folks, is just math.